Subscribe to the Newsletter

Your cart is empty

Shop now

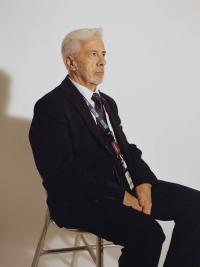

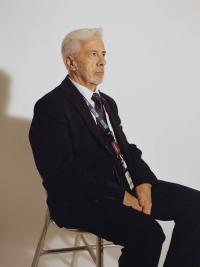

Der Greif Artist Feature Award at Fotofestiwal Łódź 2025: Q&A with Davide Sartori

“They say the shape of our eyes, other things I wouldn’t know” is a poetic investigation of intimacy, intergenerational trauma, and the father-son gaze

Our Community Manager and Program curator recently had the pleasure of reviewing portfolios at this year’s Fotofestiwal in Łódź, Poland. She selected Davide Sartori for our Der Greif Artist Feature Award, recognizing the poignant sensitivity and formal precision of his KABK graduation project, “They say the shape of our eyes, other things I wouldn’t know” (2024). Sartori, won the Premio Giovane Fotografia Italiana in 2025, was the recipient of the Public Prize at the Netherlands Fotomuseum for the Steenbergen Stipendium, and is a current participant in the FOTODOK Lighthouse Talent Program. He is an Italian photographer based in the Netherlands and his work investigates intergenerational trauma, masculinity, and the architecture of memory through a blend of documentary image-making, archival intervention, and staged performance. In this series, Sartori explores the emotional distance between himself and his father through a series of collaborative photographic “attempts,” creating a visual language that examines family, labor, and gendered expectations as both inherited and actively reshaped.

Francesca Hummler: Your project stages eleven "attempts" to connect with your father through role reversal, shared space, and observation. How did photography become a therapeutic tool for this process, and did it shift your understanding of what a rewarding father-son relationship might look like?

Davide Sartori: When I was younger, I looked at photography as a tool for representation and documentation, mostly as something that translated reality. At the beginning of the project, I started using the medium to observe my father, but while observing him, I realised that it allowed me to finally engage with him and ask those questions that, without a context or a certain intimacy, were impossible to ask. It’s at that point that the work itself took a shift; it went from an observation to an active engagement with my subject. The main role of the photographic medium was not to document anymore, but to allow the engagement, to somehow justify the time we spent together and the actions we started performing. I am not sure I had a clear idea of what a rewarding father-son relationship could look like. I think I mostly had an expectation about it defined by how it’s represented within society. Certainly, this work gave me a refreshing view on it, having a bond does not necessarily mean to play father and son out in the open.or me it is mostly about sharing an emotional connection and trying to understand each other despite our differences.

FH: Traditional masculinity often equates emotional distance with strength. By mimicking your father's gestures and wearing his uniform, you demonstrate the challenge of inheriting these tropes. How conscious were you of performing masculinity through these photographic acts, and what did your father’s response reveal about his performance of gender?

DS: While wearing his airport worker uniform, I was trying to put myself in his shoes and somehow carry the weight of his experience, or at least I tried to do so. I was aware of the performative aspect because I don’t relate to the emotional distance that was much more present in his generational experience. At the same time, my focus was to create a moment for an exchange, so I was conscious about it, but it was not my only goal; it was more of a step that was necessary to reach a point of vulnerability. His response revealed that his performance of gender was something that he learned and consequently became automatic, rather than something he was conscious about and desired.

FH: We spoke during our portfolio review about how your project resonates with Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory. To what extent have psychological theories like this influenced your approach to visual storytelling? And why do you feel photography is the most appropriate medium to navigate these intergenerational dynamics?

DS: The theoretical research in my approach is present to inform my practice, rather than directly inspiring the visual experiments, giving me awareness and allowing me to be more precise in what I want to say. Because photography can somehow present evidence from another time while maintaining its connection to reality, it creates a fertile ground for dialogue between past and present.

FH: You engage with archival material not just as historical residue, but as a co-author in your unfolding dialogue with your father. How do you conceptualize the photographic archive in your practice?

DS: The archive is one of the only ways I had to relate to my grandfather, I only know him through the labyrinth of familial gazes that exists between me and the Images in my family albums. While I also heard stories about him from my father, the photographs highlight an image of him that is more connected to reality rather than a personal experience.

FH: There’s a subtle class dynamic in the work, the contrast between your father’s uniformed labor and your artistic labor, his workplace and your studio. How do you see these spaces and their representations speaking to broader social structures of economy, aspiration, and generational mobility?

DS: My practice is the result of the mobility my parents didn’t have, but that my mother allowed me to have. I have a view on labour that has been shaped by my mother’s love and sacrifices. Which gave me more freedom and a position from which I was able to look at society and develop a critique. In contrast, my father mainly saw work as a duty, and one he did not choose to have, as his father passed away early, and he began working very young at the same airport that his father had worked at. This is reflected in the parallel between the trauma and his job, since they are both elements he inherited.

FH: The emotional arc of the work builds toward empathy, yet you also speak of fear, the fear of seeing yourself in your father. How does this project help you navigate the tension between identification and individuation within patriarchal lineage?

DS: The fear of seeing myself in him is related to the fear of inheriting his pain and struggles. Through the work, I realized that identifying myself in him doesn’t mean that I am replicating his experience but rather recognising it, and therefore becoming able to step away from it. And maybe I won’t be able to step as far from it as I would like to, but at least it gives me hope that the next generation will step even further away than I did.

FH: In both, “They say the shape of our eyes, other things I wouldn’t know” and your earlier work, Alone in the house in which I grew up, the text functions as more than a caption, it becomes an emotional and structural scaffold. What role does writing play in your practice, and how do you approach the relationship between text and image?

DS: As Barthes would say, in my practice I use text as something that carries the function of “Anchorage” directing the viewer into a specific reading, sometimes providing additional information that is not evident in the image. Instead, while researching, I mostly write down fragmented thoughts, which I then re-read afterwards and reflect upon. I don’t consider myself a writer in the sense that I naturally write, but I mostly do it as a way to re-order ideas.

FH: You've described the project as a bridge not only to your father but to "distant generations." In a time when family structures are being questioned and reimagined, going forward, how do you hope to contribute to contemporary conversations about kinship, healing, and inheritance?

DS: I believe that even though family structures are being questioned and reimagined, there aren’t enough examples of that outside of the more progressive artistic field. I hope to bring a democratic and accessible perspective on vulnerability and raise awareness about the necessity of a dialogue.