Subscribe to the Newsletter

Your cart is empty

Shop now

Der Greif X MPB: Behind the Image with Aldo Iram Juárez

Der Greif in partnership with MPB presents Aldo Iram Juárez, Guest Room Scholarship winner

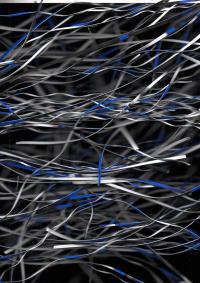

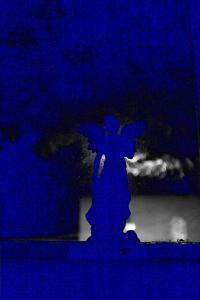

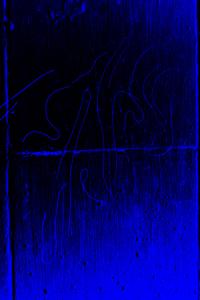

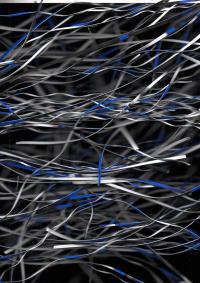

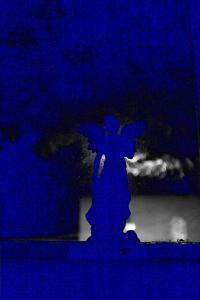

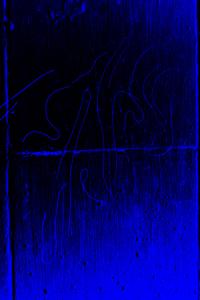

Der Greif and MPB introduce Aldo Iram Juárez, scholarship recipient from our Guest Room “WHERE is the photographic image?,” curated by Joanna Zylinska and Yanai Toister. Juárez is a photographer, artist and curator from Mexico City. His practice is rooted in an understanding of photography as a “mirage”: a projection of presumptions and desires, devoid of documentary intent or introspection – serving only the fleeting seduction of the viewer and the momentary gratification of those portrayed. His image “23082023-13,” from the series “Elogio de las ombras” and featured in Zylinska and Toister’s Guest Room, is a cameraless work that reflects Juarez’s decision to set aside the camera and pursue a more abstract approach reconceptualizing and recontextualizing his photographic archive through a range of experimental methods.

This format is brought to you in partnership with MPB, Europe’s top camera reseller.

Der Greif: Can you tell us the story behind your work selected for Guest Room?

Aldo Iram Juárez: After more than a decade of defining myself as a “photographer,” I eventually stopped taking photos altogether. While the pandemic certainly played a role in this shift, my disillusionment began earlier – rooted in the way photography, both locally and globally, had increasingly become just another tool for mass consumption. We’ve largely abandoned photography as a means of bearing witness or personal reflection, replacing it with a visual culture saturated by commercialism, narcissism, and a desire to eternalize fantasy – or all of these at once. After fifteen years of identifying as (or "being") a photographer, perhaps the most valuable thing I’ve learned is to stop taking pictures. To stop trying to turn life into images. Instead, to be present – to simply be alive and see the world with my own eyes. This shift has led me to set aside the camera almost entirely over the past three years and turn toward a more abstract body of work: reconceptualizing and recontextualizing my photographic archive through various experimental approaches. In my most recent series, “Elogio de las Sombras” (Spanish for “In Praise of Shadows”), one of the guiding principles was to create photographic work without using a camera. I worked exclusively with "recycled" images from my own archive, a home scanner, and a hands-on process of cutting and pasting. My interest was to produce work that resists easy categorization, that can’t be read, defined, or replicated (or stolen) by AI.

DG: Can you expand on the themes that your photographic work explores specifically?

AIJ: Most of my actual photographs are rooted in the domestic environment: intimate and abstract. I rarely go out "hunting" for themes or subjects, partly for the reasons I’ve already mentioned. Over the past four or five years, my approach has become less about creating traditional projects, series, or portfolios and more about engaging in visual "rituals." These are ongoing, time-based commitments (daily, monthly, or yearly) through which I explore photography as a medium. Rather than adhering to specific genres, these rituals function as personal research or visual essays that examine photography itself: its staged nature, its integration into everyday life from politics and marketing to social media and the overwhelming saturation of aspiring online “influencers”, and the evolving scale and means of image consumption in the digital age.

DG: What is the biggest challenge you have faced in photography?

AIJ: My socioeconomic background has shaped my practice significantly. I’ve never had the means to support it full-time, which has pushed me to be resourceful and creative with limited tools. What’s been more difficult, though, is gaining recognition locally. Mexico has a strong tradition of documentary photography, rooted in our long history of social and political conflict. Local and international institutions often prioritize “truthful” photo essays. But this focus has, in many ways and in my perspectives, labeled Mexican photography into a singular narrative – one that often involves staging and exploitation to meet the expectations of global audiences.

DG: Who are some photographers who inspire your work?

AIJ: Hiroshi Sugimoto and Wolfgang Tillmans were the two most influential figures during my formative years. I’ve also drawn significant inspiration from artists outside of photography, particularly On Kawara and Tehching Hsieh. These days, I find myself more inspired – and often both impressed and overwhelmed – by social media culture and aesthetics, the rise of AI, and the immersive worlds of video games.

Der Greif in partnership with MPB presents Aldo Iram Juárez, Guest Room Scholarship winner

Der Greif and MPB introduce Aldo Iram Juárez, scholarship recipient from our Guest Room “WHERE is the photographic image?,” curated by Joanna Zylinska and Yanai Toister. Juárez is a photographer, artist and curator from Mexico City. His practice is rooted in an understanding of photography as a “mirage”: a projection of presumptions and desires, devoid of documentary intent or introspection – serving only the fleeting seduction of the viewer and the momentary gratification of those portrayed. His image “23082023-13,” from the series “Elogio de las ombras” and featured in Zylinska and Toister’s Guest Room, is a cameraless work that reflects Juarez’s decision to set aside the camera and pursue a more abstract approach reconceptualizing and recontextualizing his photographic archive through a range of experimental methods.

This format is brought to you in partnership with MPB, Europe’s top camera reseller.

Der Greif: Can you tell us the story behind your work selected for Guest Room?

Aldo Iram Juárez: After more than a decade of defining myself as a “photographer,” I eventually stopped taking photos altogether. While the pandemic certainly played a role in this shift, my disillusionment began earlier – rooted in the way photography, both locally and globally, had increasingly become just another tool for mass consumption. We’ve largely abandoned photography as a means of bearing witness or personal reflection, replacing it with a visual culture saturated by commercialism, narcissism, and a desire to eternalize fantasy – or all of these at once. After fifteen years of identifying as (or "being") a photographer, perhaps the most valuable thing I’ve learned is to stop taking pictures. To stop trying to turn life into images. Instead, to be present – to simply be alive and see the world with my own eyes. This shift has led me to set aside the camera almost entirely over the past three years and turn toward a more abstract body of work: reconceptualizing and recontextualizing my photographic archive through various experimental approaches. In my most recent series, “Elogio de las Sombras” (Spanish for “In Praise of Shadows”), one of the guiding principles was to create photographic work without using a camera. I worked exclusively with "recycled" images from my own archive, a home scanner, and a hands-on process of cutting and pasting. My interest was to produce work that resists easy categorization, that can’t be read, defined, or replicated (or stolen) by AI.

DG: Can you expand on the themes that your photographic work explores specifically?

AIJ: Most of my actual photographs are rooted in the domestic environment: intimate and abstract. I rarely go out "hunting" for themes or subjects, partly for the reasons I’ve already mentioned. Over the past four or five years, my approach has become less about creating traditional projects, series, or portfolios and more about engaging in visual "rituals." These are ongoing, time-based commitments (daily, monthly, or yearly) through which I explore photography as a medium. Rather than adhering to specific genres, these rituals function as personal research or visual essays that examine photography itself: its staged nature, its integration into everyday life from politics and marketing to social media and the overwhelming saturation of aspiring online “influencers”, and the evolving scale and means of image consumption in the digital age.

DG: What is the biggest challenge you have faced in photography?

AIJ: My socioeconomic background has shaped my practice significantly. I’ve never had the means to support it full-time, which has pushed me to be resourceful and creative with limited tools. What’s been more difficult, though, is gaining recognition locally. Mexico has a strong tradition of documentary photography, rooted in our long history of social and political conflict. Local and international institutions often prioritize “truthful” photo essays. But this focus has, in many ways and in my perspectives, labeled Mexican photography into a singular narrative – one that often involves staging and exploitation to meet the expectations of global audiences.

DG: Who are some photographers who inspire your work?

AIJ: Hiroshi Sugimoto and Wolfgang Tillmans were the two most influential figures during my formative years. I’ve also drawn significant inspiration from artists outside of photography, particularly On Kawara and Tehching Hsieh. These days, I find myself more inspired – and often both impressed and overwhelmed – by social media culture and aesthetics, the rise of AI, and the immersive worlds of video games.DG: What are you working on right now?

AIJ: started this year with a new series that combines personal archive photographs and text, titled With Captions (For the Visually Impaired). I also plan to end my three-year hiatus from using a camera, upgrade my gear (thankfully, I discovered MPB around the same time!), and begin creating new images.

DG: What kind of gear do you work with?

AIJ: I work with the oldest, cheapest lo-fi equipment I can get my hands on. My weapon of choice is a Canon Digital Rebel from 2003 – my very first DSLR. It’s slow, unpredictable, and sometimes doesn’t even take the photo! But using it feels like a ritual. It’s like one of those old cars only I know how to start – unreliable in a charming way. The grain from the high ISO is beautiful. Cameras from that era didn’t try so hard to hide digital noise, so the texture feels almost like film. I’ve even removed the screen preview and swapped out the original lens. These days, I mostly use it with an SMC Pentax 1:2.8 24mm or with cheap plastic adapters for macro and other experiments. My other main photographic tool for the past five years has been my home scanner.

DG: What was the first camera you ever used?

AIJ: The very first camera I ever used was probably my family’s old 110 or 35mm film camera. But the first one I used for my own work as an artist was a Canon PowerShot – I think it was the A460 version.

DG: What do you value in your camera gear today? Any thoughts on used gear?

AIJ: I love used gear – I think that’s pretty clear by now! Beyond personal preference, I believe it’s important to move away from the cycle of constant tech production and consumption. The world simply doesn’t need more of it every year. That’s why platforms like MPB are so valuable: they make it possible to access used equipment from around the world. It gives us the chance to a) try out gear we’ve always wanted at a more affordable price – whether it’s a big camera for a specific project or just something new to play with – and b) experiment with different formats, brands, and even eras (I’ve mentioned how much I love “old” cameras) that can open up new creative possibilities.

DG: Can you tell us what this scholarship means for you?

AIJ: This might just be the thing that reignites my photographic career — for all the reasons I’ve mentioned. It’s an incredible opportunity to share my work beyond Mexico (and on Der Greif, no less! I’ve long admired your work). This opportunity also gives me the tangible support I need to move forward: maybe now I can finally buy a new camera or produce more prints for my next series.

In partnership with our Guest Room partner