Subscribe to the Newsletter

Your cart is empty

Shop now

Greif Alumni: Q&A with Bacci Moriniello

Bacci Moriniello on AI-generated images and the photographic

We periodically invite our alumni, artists we have featured in the past, to share their new work and projects with us. Bacci Moriniello is an artist duo consisting of photographers and researchers Lorenzo Bacci and Flavio Moriniello, who were featured in our Guest Room curated by Holly Hay & Olivia Hazeldine & Sophie Gladstone in 2020. Since 2019, they’ve employed a multidisciplinary approach in their research, with a specific focus on examining the intricate relationship between humans and technology. Their work is in both public and private collections such as MUFOCO (Milan) and Centre Claude Cahun Contemporaine (Nantes).

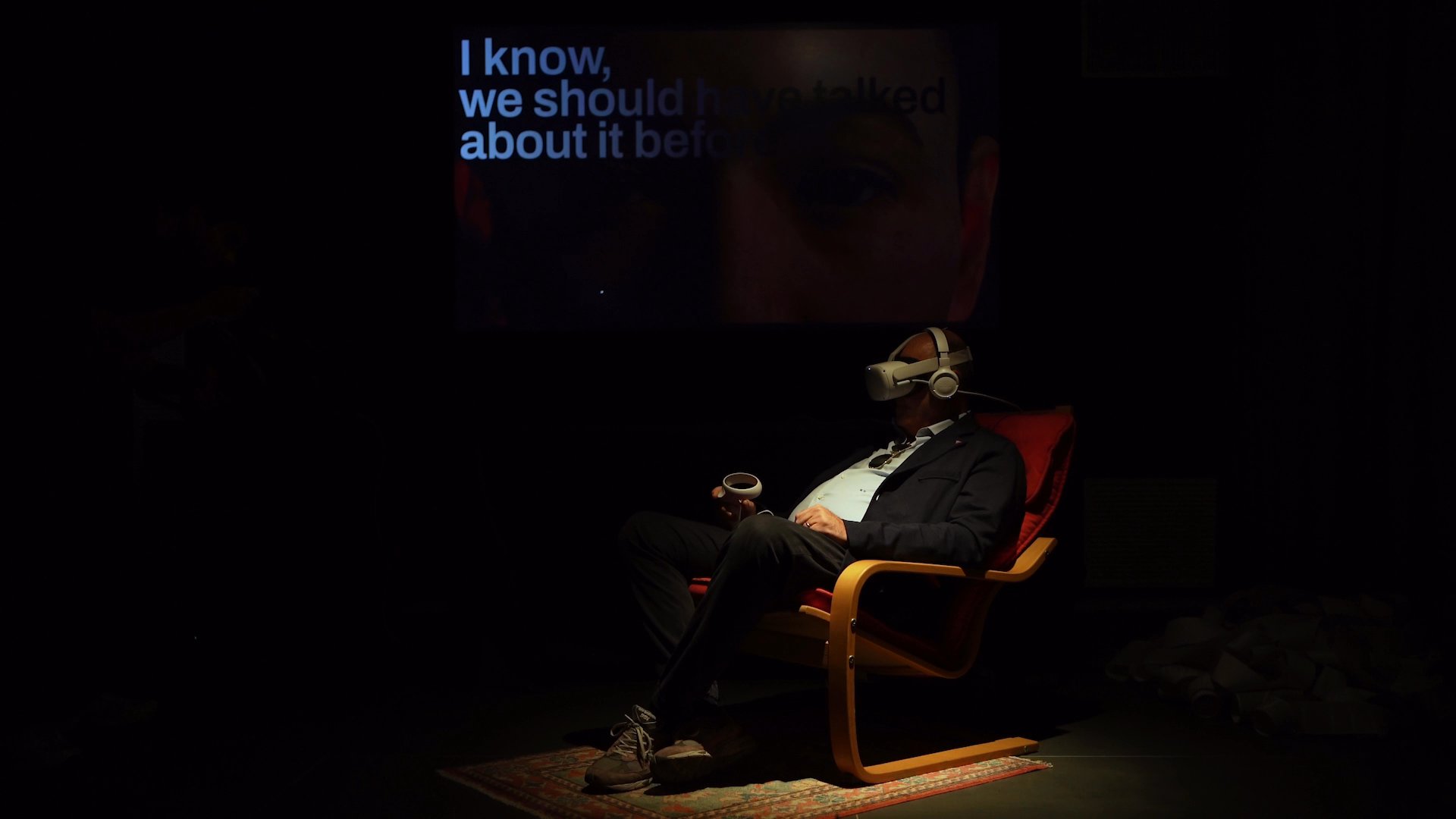

Bacci Moriniello recently presented a performative and interactive work entitled "I Know, We Should Have Talked About It Before", which took place in September at FestivalFilosofia in Modena (Italy) as part of a visual arts program curated by Chiara Spaggiari, Cristina Lanzafame and Federica Benedetti.

Ilaria Sponda: Could you introduce us to your most recent project “I Know, We Should Have Talked About It Before”?

Bacci Moriniello: “I Know, We Should Have Talked About It Before” is a deeply immersive experience that combines art, technology, communications, and human-machine relationships. The project unfolds in a virtual reality (VR) environment created with Unreal Engine, where visitors navigate through an undefined, symbolic space that reflects the complexity of interactions and representations. The foundation of the project lies in dialogue, exploring two equally significant conversations: the first, between the user and an artificial intelligence, and the second, among humans themselves. The aim is twofold: to introduce the audience to the potential of this technology while critically exploring its current limitations and future implications. At the heart of the experience lies a custom-designed AI chatbot built to engage participants in exchanges that evoke the emotional nuances of unresolved dialogues. These conversations are intended to delve into deeply personal and introspective dimensions of the spectators’ experiences. The VR space itself acts as a metaphorical landscape, filled with symbolic objects and scenarios in which participants are immersed. Each interaction with the viewer generates a different dialogue, addressing new themes every time. We presented the project at FestivalFilosofia in September in Modena (Italy), a setting where even the participants who didn’t wear the headset played a crucial role in the work by constructing an observation of other people interacting with the machine and reflecting on the fragility and resilience of humanity in an increasingly mediated world.

IS: What's left of the "photographic" in your current practice exploring VR worlds and AIs?

BM: In our current practice, photography remains a foundational element, particularly for the theoretical and conceptual insights it has provided us. Photography is one of the first technologies allowing for the creation of images in an automated way—a precursor to the technologies that are now emerging as mass tools in this historical period. Furthermore, photography inherently relies on the relationship between the observer and the observed. For some, this is a unidirectional relationship, while for others, it is bidirectional and therefore actively involves both sides. Similarly, in our projects, the user assumes a central role—choosing what to focus on and how to interpret both the physical and virtual environments we create. It is important to note that each project has both a physical and a virtual/fictional environment. This active participation mirrors the subjective experience, emphasizing the user's agency in shaping meaning. Themes central to our photographic practice—such as perception, memory, and the construction of reality—are seamlessly carried over into our projects. Through the use of AI and VR, we are able to push these ideas even further, challenging conventional notions of documenting or creating in a world where the boundaries between the real and virtual increasingly blur.

External Content

We are displaying external content here, and in that way, personal data is transmitted to third-party platforms. DER GREIF has no influence on this. You can read more about this in our privacy policy.

IS: Could we state that "photography" is still there in your works as an informative apparatus and nature of image representing a double to reality?

BM: Even as we move into VR installations and AI-driven experiences, the photographic persists in its nature of representing a sort of doppelganger of reality, a tool for interpreting, questioning, and constructing the world around us. Photography’s ability to document and mediate reality informs how we construct our visual and narrative worlds. The medium's intrinsic link to truth and representation underpins our approach, whether we’re generating AI images or designing VR environments. In VR, the photographic shifts its status from a static representation into a dynamic simulation composed of nothing but images. We are assisting an “environmentalization of the image,” quoting Andrea Pinotti.The environments we create remain informed by photographic principles—composition, light, texture—but extend these into interactive, immersive spaces. This shift doesn’t negate photography; rather, it expands its capacity to engage with reality on multiple levels. During the show at FestivalFilosofia, we chose to show the backstage of our research, exhibiting an apparatus of images spanning from photographs, in-game screenshots, and blueprints of both the level design and character design.

IS: From “Brave New World” to “I Know, We Should Have Talked About It Before” there's an evolution in the output: from AI-generated images to VR installation and text. Both speak of a coherent feature in all your artistic oeuvre. You position your constructed worlds in between possible futures and past windows of time: you suggest this not only through your work titles always referencing time gaps but also through the imageries you craft. They result in being the mirror of what the present is today: an imperceptible lapse, an "extreme present" (Basar, Coupland, Obrist, 2015). In which temporal tense would you position your works?

BM: Our works exist in a deliberately ambiguous temporal space—a liminal zone where past, present, and future converge. Rather than being anchored in a specific temporal tense, they inhabit what you’ve correctly referred to as an "extreme present," a condition where time collapses under the weight of hyperconnectivity, technological acceleration, and the fragmentation of narratives. This approach is intentional. In general, we aim to challenge the viewer's perception. The imagery and narratives we create aren’t about predicting the future or reconstructing the past—they’re about making visible the forces shaping the now, forces often too vast or subtle to perceive. These projects suggest that what we see as the future or past is a reflection of the beliefs, biases, anxieties, desires, and contradictions of the present moment. The past and future in our works are not endpoints but mirrors that reflect the intricate dynamics of the present.

IS: How has your work with images, photographic images, changed since AI latest developments and its mainstream uses?

BM: AI's integration into mainstream tools has transformed how we approach working with images, expanding creative possibilities while prompting critical reflection on the boundaries of photorealistic representation. We’re now collaborating with AI to generate imagery from datasets, algorithms, and prompts, blurring the lines between reality and construction. This shift requires a new literacy—understanding AI’s biases, limitations, and potential as a creative partner. As AI-generated images mimic photographic reality, questions about truth, mediation, and the meaning of creation in a technologically saturated world become central. AI has also shifted our focus from static images to dynamic, generative systems, aligning with explorations in VR and interactive media and challenging ideas of ownership and raising questions about creativity and copyright. This evolving tension reflects broader cultural anxieties which inspire future themes in our practice.