Subscribe to the Newsletter

Your cart is empty

Shop now

Behind the Curtain

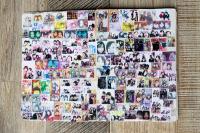

‘Purikura’ is a type of photobooth that emerged in Japanese arcades during the 1990s, distinct from the standard booths that had existed before. Designed to appeal to a young female audience, Purikura aimed to draw them back into arcade culture. These booths allowed users to take photographs and print them as small sticker-like images, which they could exchange with friends and collect in personalized books.

Purikura quickly became a sensation among young girls. By the summer of 1997, there were 45,000 Purikura booths across Japan. Over time, features like graffiti, symbols, and decorative stamps were introduced, sparking creativity and making the experience even more engaging (Hunt 2018.)

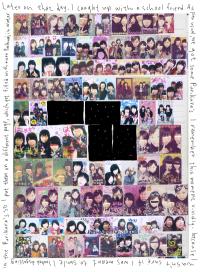

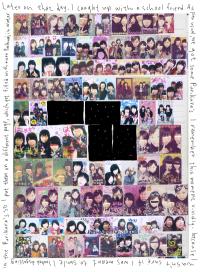

Growing up during the height of the Purikura boom, my social life revolved around these booths. After school and on weekends, we would visit the arcade to take Purikura photos – not just to capture cute images of ourselves but to annotate them with bold statements, relationship or friendship statuses, inside jokes, or notes about our crushes.

We carried our Purikura books everywhere – to school, cram school, and friends’ houses. Girls would gather and spend hours flipping through each other’s collections. It was our version of social media before the digital age fully took over.

For my series Weapon of Choice, I have been experimenting with my old Purikura images. They may not make it into the final project, but revisiting them evokes a lump in my throat, as they capture raw, unfiltered emotions.

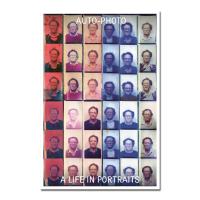

In “Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits”, Pound wrote something that resonated deeply with me:

“Unlike the commercial photographic studio, in the photobooth, the sitter is in control. When you pull aside the curtain and commit to having your image taken, you get to choose how to look. But then again, that control is a matter of timing, chance, and luck. It is the untimely and indiscriminate shutter that gives so many of these photographs their charm and charge.” (Pound 2023, 7)

Purikura gave young girls a sense of control—they could shape their image, define their status, and momentarily escape reality once the curtain closed. For a few minutes, it became a perfect playground for teenage girls, a space where they could present themselves however they wished.

While smartphones and social media have transformed the way Purikura is presented, its essence and purpose remain deeply embedded in Japanese youth culture.

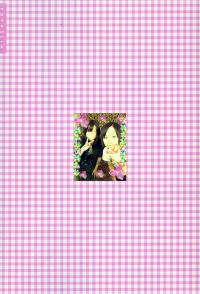

Looking back at the Purikura from that particular summer, the images suggest a carefree break with my girlfriends. But beneath the surface, I felt dirty, ashamed, and desperate – longing for someone to notice, to pull me out of my misery, because in real life, I couldn’t close the curtain.

References;

Hunt, J 2018, “How ‘Playing Puri’ Paved the Way for Snapchat”, BBC, accessed 11 January 2025.

Pound, P 2024, “Photography without photographers”, in D Boetker-Smith & C Langford with Metro Auto Photo (eds), “Auto-photo: A Life in Portraits”, Centre for Contemporary Photography & Perimeter Editions, Melbourne, pp. 5-11.

Minami Ivory is part of »Guest Room: Aaron Stern«

Check out her Artist Feature Weapon of Choice.