Subscribe to the Newsletter

Your cart is empty

Shop now

Photography’s Vague Claim to Truth

Discussing the concept of truth in photography

„Every photograph is a fiction with pretensions to truth“ - Joan Fontcuberta

Since its invention in the 19th century the photographic process and the medium photography have always been understood as a machinery depicting an excerpt of reality. From a more clarified point of view this connection between photography and reality has always been rather loose and random and depending a lot on the intention of the author, the photographer.

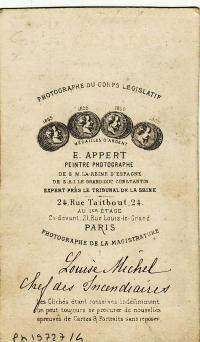

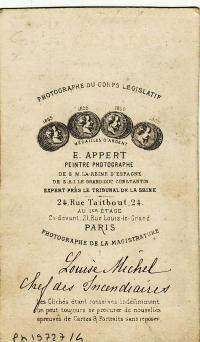

An early interesting example for the usage of the medium and the bending of reality would be offered by French Photographer Eugene Appert (1830 - 1905). Long before the possibilities of Photoshop diminished the trust in photography as a confidable medium, Appert had made up visual deep fakes when he created his imagery covering the uprising of the Commune de Paris in the 1870s.

In order to get an idea about different motivations behind the usage of visuals, we will have a closer look at the imagery relating to the detention of Louise Michel, a female anarchist and one of the leaders of the communards, on the orders of the Versailles government in 1871.

Image number one shows an oil painting by Jules Girardet, created in 1871, shortly after the historic event.

Image #1

Composition and lighting in the painting probably were more important for the artist than the idea of creating a realistic document, but still back in the nineteenth century paintings were a source considered to be documentary.

At this time, Eugene Appert was hired by the police to take photographs of delinquents for future tracing, so he took pictures of the left and right profile and front of Luise Michel (image #2 + #3). This marked the historic invention of the mugshot.

Image #2 + #3

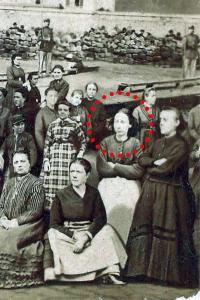

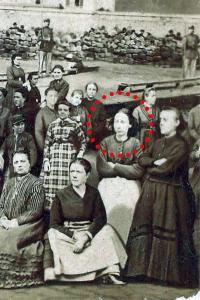

For his “journalistic” work for newspapers and for the portfolios he sold, Appert created image #4, a photomontage combining several portraits of delinquents. You can find Louise Michel in the right foreground of the picture (image #4 + #5).

Image #4 + #5

Looking a bit closer to the image, we find quite obvious hints that this image doesn’t show realistic scenery, but is a composition of several elements, a collage. An easy proof for that is for example the unrealistic repetition of single elements, like clothing, in the image (see image #6)

Image #6

What Appert wants to tell with this collage is the story of a group of defiant women, dressed up, celebrating and drinking alcohol - a scenery that’s quite different from the impression we get when looking at the mugshot of the gaunt Louise Michel. With our visual experience nowadays it isn’t much of a challenge to debunk this collage, but how was it read in 1871?Appert’s intention was to create visuals that could be read as real - he mimicked optical phenomena like spatial depth and perspective. With this image and other collages Appert wanted to communicate and demonize the actions of the Commune de Paris.

In a next step I tried to add another level of simulation and distortion to this historic incident, using the latest technical development in generating visuals: I asked A.I. to produce a portrait of Louise Michel. The exact prompt for Adobe Firefly was: “A portrait of Louise Michel taken at the prison Chantiers de Versailles, Paris 1872.”

Image #7

Intriguingly, the overall appearance of the A.I. generated picture is much closer to that of Appert’s biased collage than to his mugshot of Louise Michel. I wouldn’t say A.I. has deliberately tried to create a wrong document of the Paris riots, but the interesting aspect about this generated image is that its aesthetics are strikingly close to Appert’s propaganda collages (although it’s not clear if Appert’s montage is already part of A.I.’s source library, nor did I prompt towards this look). Perhaps the algorithm is more after pleasing visuals than it is after content and authenticity.

Still, this generated picture is in some aspects a photograph, as it uses photographic language, is based on a library of millions of photographs and wants to be read as a photographic image: So it flirts with photography’s claim to truth, even if it has not been taken with a camera - while Appert’s tools were analogue and very classic.

Which of the images is closer to the truth? Which one is more qualified as a source for an evaluation of a historical incident? Are the various image sources differing in verisimilitude anyway? Probably the answers to these questions depend less on how the images have been produced, but more on how we read them.

Jens Masmann is part of »Guest Room: Michael Famighetti«.

Check out his Artist Feature Ping Pong.