Subscribe to the Newsletter

Your cart is empty

Shop now

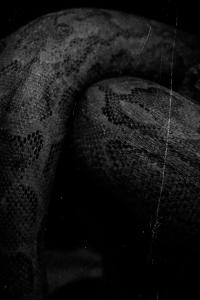

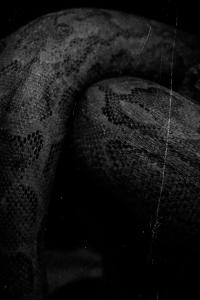

Presence

“‘Presence’ functions as a fluid record of the patriarchal (il)legibility of women’s histories of persecution. Read through Silvia Federici’s analysis of witch hunts as foundational acts of capitalist violence, the work exposes how systems of bodily governance and extraction persist, structuring women’s lives long after the violence itself has been historicized. By recombining archival images with personal photographs, Silverj displaces violence from regimes of documentation and reactivates it within new visual dialogues through a personal, yet undisclosed and cryptic perspective. Hands recur as charged gestures among symbols and icons binding women across generations like bloodlines. I see women’s presence emerging from darkness as an index of what happens to our imagination under conditions of repeated, witnessed or experienced violence: when seeing falters, thought fractures, and images of memories glitches. As violence turns into a recurring visual imprint, it lingers in the imagination as something at once omnipresent and unprocessable. In this collapse of perception, women risk both stopping seeing and stopping being seen. How do we appear within profound darkness, when violence interrupts not only vision but the capacity to imagine otherwise? What practices of presence allow us to resist disappearance?” (Ilaria Sponda)

On August 29, 1523, Margherita, known as Madregna, was accused of witchcraft. Tortured with rope, she confessed to practicing sorcery and attending a sabbath. She was condemned and burned alive at the stake. Her property was seized and redistributed according to Inquisitorial customs. Centuries later, her voice still echoes.

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, fear and superstition took root across Europe, fueling the systematic persecution we now call the witch hunts. These were not isolated moments of hysteria, but sustained campaigns rooted in political, religious, and social control. The main targets were women, midwives, healers, widows, the poor, those who defied the roles assigned to them. Accusations could arise from almost nothing: a fever, a failed harvest, a neighbor’s envy. Folk rituals, knowledge of plants, or even physical traits became evidence of a pact with the devil. Witchcraft was the name given to any form of female autonomy.

The Inquisition and civil tribunals developed legal systems to prosecute these so-called witches. Torture was used to extract confessions confirming a worldview that needed enemies. Manuals like the “Malleus Maleficarum” shaped both ideology and method, legitimizing violence in the name of moral order. Though men and children were also accused, nearly two-thirds of those tried were women. Their bodies were inspected in search of “devil’s marks.” Their deaths, by fire, hanging, or torture, were meant to serve as public warnings. Fear had to be made visible. The last execution for witchcraft in Europe was that of Anna Göldi, in 1782, but the mechanisms of control persisted.

Centuries later, in fascist Italy, women who resisted prescribed domestic roles were confined to asylums, branded “malacarne” (“bad flesh”” and cast as threats to state ethics. What had once been heresy became pathology. Emotion itself was medicalized, punished, and used as justification for confinement.

Even today, the logic of punishment remains. Femicide is the brutal echo of those fires. Women are still burned alive, symbolically and literally, for refusing submission. They are killed by partners, ex-partners, family members. The methods have changed, but the meaning has not.

“Presence” is not just about the history of women’s persecutions. It is about legacy and as such, it demands reckoning, not in numbers alone, but in memory, voice, and justice.

Alessandro Silverj took part in our Face-to-Face educational feedback program with Managing Editor Ilaria Sponda. Silverij is also part of »Guest Room: Christine Marie Serchia & Charlotte Jansen«.